Russia has adopted the most extreme version of Eurasianism (Neo-Eurasianism) that has led to its blunder with Ukraine. The ramifications will exacerbate the disintegration of Eurasia.

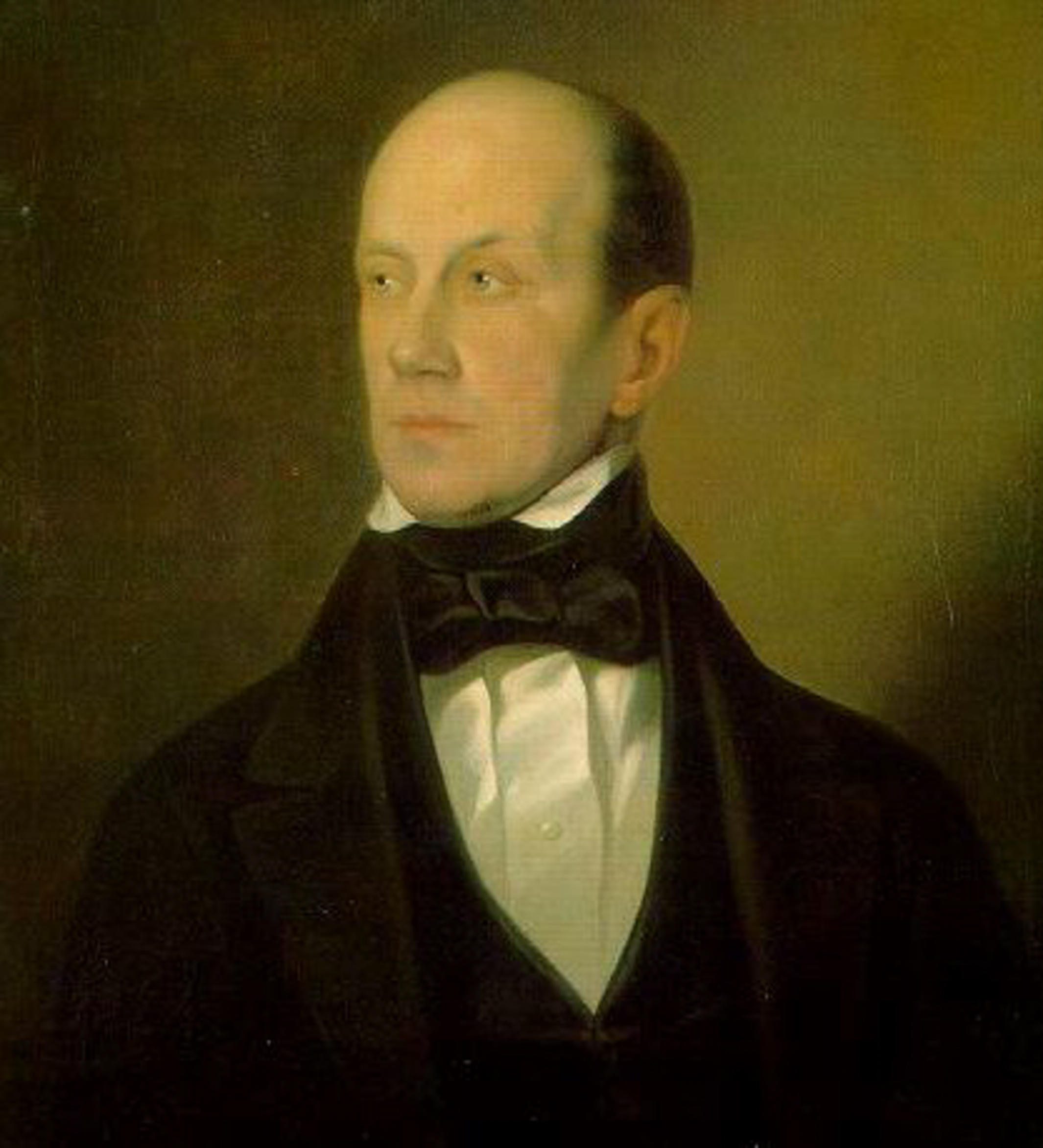

“We belong to none of the great families of mankind; we are neither of the West nor of the East” – Pyotr Chaadayev

The origins of Russian Eurasianism

The origin of Russian Eurasianism begins with Russia’s historical imperialist legacy within Asia. From Peter the Great with the Russian Empire to The Soviet Union. The political philosophy emerged and developed due to Russia’s shared civilisational cultural history with both the West & East which established the perspective that Russia doesn’t belong to either. Russia has its own civilisation and national identity that is not European nor Asian but Eurasian. The man that started it all was Pyotr Chaadayev after the publication of his contentious Philosophical Letters & Apology of a Madman depicting Russia as a world that is separate from Europe and Asia. This spilt the Russian intellectual elites into two camps having very different approaches towards Russia’s national identity and place within the world between West & East between Europe & Asia.

The two camps were the Slavophiles and the Westernizers who both have their beginnings from the 1812 war against Napoleon’s invasion of Russia. Both emerged in the 1830s with the aftermath of the French Revolution and the universal culture of Enlightenment. The Slavophiles rejected the nuance European revolutionary liberal ideals for religious traditions, national customs and ethnic culture. After the failed Decemberist revolt of 1825 for a constitutional monarchy the Slavophiles saw Slavic Orthodoxy as what distinguishes Russia from the West & East. The Westernizers embraced the West and saw Russia apart of Europe. After Russia’s Civil War and the Bolsheviks Revolution exiles from the Slavophile school of thought came together in Europe to elaborate on how the Soviet Union could emulate the Russian Empire. These immigrants were Pyotr Savitsky (economic geographer & geopolitician), Prince Nikolai Trubetzkoy (linguist & philosopher), Georges Florovsky (theologian & historian) and Pyotr Suvchinsky (musicologist & art critic). They were influenced by Halford Mackinder’s The Geographical Pivot of History and saw Russia at the heart of Eurasia.

They published their manifesto Exodus to the East: Forebodings and Events: An Affirmation of the Eurasians and many articles that formed the foundation of Russian Eurasianism (Classical Eurasianism). The Eurasianists hated the atheism and materialism of Marxism but appreciated the statism and autocracy of the Soviet Union. They saw the Bolshevik Revolution as a part of Russia’s historical rebellious reformist nature and character but undermined Russia’s religious ethnic culture. They wanted the Soviet Union to represent the religious culture (Orthodoxy) and multi-ethnicity (Slavic, Finno-Ugrian and Turkish) of the Russian civilisation and Russian Empire. Many joined and collaborated with the Eurasianist movement including Lev Karsavin (philosopher & historian), Konstantin Chkheidze (writer & philosopher), Prince Dmitry Sviatopolk-Mirsky (literary historian & translator), Sergei Efron (poet & officer of the White Army), Pyotr Arapov (military personnel), Nikolay Ustrialov (National Bolshevik) and Vsevolod Ivanov (writer). The Eurasinaists wanted to influence even replace the Soviet elites and Marxism with Eurasianism as a unifying state ideology that united Russia with its near abroad neighbours under the Soviet Union.

Within the Russian context Eurasianism as a political ideology is simply religious cultural socialist transnationalism. Chkheidze provided the Eurasian analysis of the ethnic cultural nationalities problem on the territory of the former Russian Empire. State cohesion requires a number of substantive prerequisites including geopolitical unity, ethnic unity and cultural historical unity. Chkheidze viewed that all these necessary prerequisites were present in Russian Eurasia as an assemblic unity (sobornost) being the core ideal of Russian Eurasianism. The Eurasianist movement ended due to infighting among their members over many different reasons. Russian Eurasianism was archived and then was renewed by Lev Gumilyov (historian, ethnologist & anthropologist) and the Russian New Right during the 1980s and 1990s when the Soviet Union was facing disintegration. Putin attended a study circle on Gumilyov’s Eurasianist school of thought during the end of the 1990s and has shown much appreciation of Gumilyov. Gumilyov pioneered ethnogenesis (the ecology of ethnicity) and declared he was the last of the Eurasianists. What came after Gumilyov was the rise of the New Right Eurasianists that saw Russia being renewed as a Eurasian power.

The New Right & New Eurasianism

The European New Right (Nouvelle Droite) led by Alain de Benoist (journalist & philosopher) collaborated with the Russian New Right to philosophically politicise ethnicity and culture. This was to find alternatives to liberalism and modernity by constructing nuance political forces and ideologies. This coalition created the red-brown alliance between Russian nationalists and communists that opposed Boris Yeltsin’s economic reforms early in the 1990s. The Russian New Right saw religion fundamentally important to the identity of Russia instead of the European New Right adopting paganism. The Russian New Right renewed Russian Eurasianism into Neo-Eurasianism creating the New Right Eurasianists. The New Right Eurasianists vision is to renew Russia as a Eurasian power building ties with religious ethnic communities and nations within Eastern Europe, Middle East and Central Asia.

The leaders of the New Right Eurasianists are Alexander Dugin (occultist philosopher & PR for GRU), Alexander Prokhanov (geopolitical novelist) and Gennafy Zyuganov (geopolitician & leader of the communist party in Russia). Vladimir Zhirinovsky (populist geopolitician) and Alexander Panarin (philosopher) were also leaders of Russian New Eurasianism. There are many politicians, academics, journalists, soldiers, media pundits, online figures and activists that are under the bander of Russian Eurasianism. Dugin has elaborated on many Eurasianist strategies for Russia to achieve great power status and bring forth the multipolar world order. In Dugin’s book Pop-Culture and the Sign of the Times he proclaims Internet Eurasia where Eurasia is not just a political economic geographical concept but also a virtual internet geography. The internet is the weapon for revolutionaries against the hegemonic liberal world order. Dugin has contributed mysticism, aryanism, occultism, ethnosociology, cosmology and conspirology to Russian Eurasianism. Dugin was fascinated by how the American neoconservative elites ended up in powerful positions during the Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush and George W. Bush administrations dictating America’s foreign policy. Dugin saw that the Eurasianists could do the same in Russia.

Prokhanov fantasises in his books (Mr. Hexogen, The Symphony of The Fifth Empire: Imperial Crystallography & The Cruise Liner Joseph Brodsky) that Russian patriots of the FSB & KGB overthrow the Jewish oligarchs and transform Moscow into the Third Rome into the New Jerusalem. He views Russia in a race war against America, Europe, China and the Jews. He believes Russia should assert its ethnography against different ethnic groups including the Chinese, the Jews, the Europeans and the Anglo-Saxons. That the role of Russian literature and language is crucial for nation building and reconstructing the Russian Empire. Zyuganov views Russian communism and Russian Eurasianism as one as the same (Eurasian socialism). He combined nationalism, orthodoxy and Marxism together to reinvent the Russian Communist Party. His book The Geography of Victory is a geopolitical manifesto that abandons anything resembling Marxist Leninism. Another book of his The Geography of History coordinates global class struggle with the division between West & East. Zhirinovsky simply believed in Russian hard power against America and its allies. In his book Last Thrust to the South he outlines Russia’s geopolitical influence expanding towards the Indian Ocean and the Persian Gulf.

The New Right Eurasianists believe war between Russia and America including its allies and NATO is inevitable which is Russia’s eschatological messianic destiny. They suggest Russia should unite with Islamic and Asian civilisations to banish western influence from Eurasia. Also have an alliance with radical Islam (particularly with Iran’s Shia bloc axis of resistance) to safe guard Russia’s interests against its competitors (Turkey, India and China) within Eurasia. They predict engineered colour revolutions throughout Eastern Europe right across Central Asia to destabilise Russia. Russia must counteract with its strategic security Eurasianist strategy to intervene and crush any up risings. The New Right have suggested coalitions between far-left and far-right forces to revolt within Western Europe to preserve ethnic culture and overturn liberalism. Dugin has advised against this for Russia since it would fragment Russia’s geopolitical position within Eurasia suggesting the Eurasianist position. After the annexation of Crimea Dugin was disappointed that Putin didn’t invade and take over Ukraine. He advocated that western liberals and Russian Eurasianists should unite to overthrow Putin. Dugin has criticised Putin over many things including Putin’s support for America’s war on terror and lack of understanding and appreciation for the Russian culture (Old Believers of Russia). If Putin is not going to fulfil the Russian Eurasian Dream, then he should be removed from power.

There are many different versions of Eurasianism that oppose New Right Eurasianism (Neo-Eurasianism) including Pragmatic Eurasianism (Russia shares Europe & Asia and West & East together), Intercivilisational Eurasianism (Russia is a combination of many civilisations) and Asian Eurasianism (Russia is Asian and apart of the East). Asian Eurasianism dictates that the religious ethnic cultural demographics of Central Asia (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Mongolia) where the ones that contributed significantly towards building the Russian civilisation, the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union more so than the Russians are willing to admit. Their ancestors went to the front lines to fight against Napoleon’s army not just the Russians. The Eurasian identity for Russia became prominent not just because of its shared history between West & East but also because of concerns of repeating Islamization and Asianization of Russia.

For more of an analysis on Alexander Dugin and the New Right please read this article: https://www.dailyscanner.com/alexander-dugin-the-eurasian-occultist/

Apocalyptic Geopolitics & The End of Eurasia

Strategic culture has become the justification of foreign intervention for great power status. Russia’s strategic culture (Eurasianism) is tied to its military security and geoeconomic energy policies that have certain ramifications for Eurasia and global security. Certain flashpoints await the disintegration and balkanisation of Eurasia. The events that have occurred with Ukraine and Kazakhstan are only the beginning of a much larger continuation of great powers colliding against each other. After the disastrous American withdraw from Afghanistan with a re-assertive Taliban you can expect the same with the withdraw from Iraq and Syria. Where Turkey will make their crucial moves against Iran. Turkey views Syria as Russia sees Ukraine the same goes for China with Taiwan. Syria is not a sovereign nation and belongs to Turkey. Turkey wants to be a great power implementing Neo-Ottomanism, Pan-Turkism and Pan-Islamism charting its course from the Middle East right throughout Central Asia. Turkey taking over Syria and moving against Iran with the help of Azerbaijan and Israel is a part of Turkey’s imperialist ambitions. Turkey supports geostrategic political Islam pioneered by Yaqub Zaki (journalist & academic) and Geydar Dzhemal (philosopher).

There were prospects that the Russian Eurasianists could encourage the Turkish Eurasianists to form a Eurasian alliance between Turkey, Russia, Iran and China. Getting Turkey to leave NATO and creating a counter-hegemonic Eurasian bloc against American hegemony. Despite the recent rapprochement between Turkey and Russia the transition has not manifested for many different reasons including Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The Neo-Ottomanist’s interpretation of Turkish Eurasianism designates that Eurasia belongs to Turkey given the historical religious cultural ties from the Ottoman Empire. Turkey supports Ukraine particularly the Crimea Tatars against Russia and is utilising NATO membership for Sweden and Finland to end support towards the Kurds. The stage is set for a showdown between Turkey and Russia within Syria, Caucuses and Central Asia (Neo-Ottomanism vs Neo-Eurasianism).

Russia for its own security and interests will have to decide whether its viable to continue its support towards Iran, Syria and Armenia instead of negotiating with Turkey, Israel and America against Syria, Iran and China. Russia is concerned about the prospect of Islam or China taking over Russia. Russia cooperating with America would securitise its Eurasianist interests within Eurasia. However, the different competing projects between Russia (Eurasian Economic Union), China (Belt & Road Initiative), Turkey (Turkish Union) and America (global liberal hegemony) will result in further conflicts, revolts and disintegration. Uzbekistan is a strategic importance for Turkey as the gateway towards Central Asia. The resources of the Caspian Sea vitally important for the great powers. The Muslins of Central Asia will not tolerate Russia, China or America to continuously support the oppressive regimes within Central Asia during economic hardship.

The disintegration and balkanization of Eurasia is the result of uneven economic development and extortion of the most vulnerable for cheap labour. It’s the continuous crisis of capitalism, globalisation and imperialism under geopolitics and geoeconomics to consolidate wealth and power for elites at the detriment of humanity. The solidarity between the good will of the many will be the purveyor over the despair within the world.

References

Donnelly, Alton S. 1975. Peter the Great and Central Asia. Canadian Slavonic Papers/Revue Canadienn des Slavistes. Vol. 17, No 2/3. Russia and Soviet Central Asia. Pp. 202-217.

Znamenski, Andrei. 2011. Red Shambhala: Magic, Prophecy and Geoplitics in the Heart of Asia. Theosophical Publishing House. Quest Books.

Heinzig, Dieter. 1983. Russia and the Soviet Union in Asia: Aspects of Colonialism and Expansionism. Contemporary Southeast Asia. Vol 4. No 4. Pp 417-450. ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute. JSTOR

Brun-Zejmis, Julia. 1991. Messianic Consciousness as an Expression of National Inferiority: Chaadaev and Some Samizdat Writings of the 1970s. Vol 50. No 3. Pp 646-658. Cambridge University Press. JSTOR

Piveronus, Peter J. 2009. Reinventing Russia: The Formation of a Post-Soviet Identity. Chapter 4 Eurasianism: The Mackinder Thesis Revisited. University Press of America. Lanham; Plymouth

Clowes, Edith W. 2011. Russian on the Edge: Imagined Geographies and Post-Soviet Identity. Chapter 2 Postmodernist Empire Meets Holy Rus’ How Alexander Dugin Tried to Change the Eurasian Periphery into the Sacred Center of the World. Cornell University Press. Ithaca & London.

Shlapentokh, Dmitry. 2017. Alexander Dugin’s views of Russian history: collapse and revival, Journal of Contemporary Central and Eastern Europe, 25:3, 331-343. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group

Shnirelman, Viktor 2001. The Fate of Empires and Eurasian Federalism: A Discussion between the Eurasianists and their Opponents in the 1920s. Inner Asia 3. 153–73. Brill.

Vinkovetsky, Ilya 2000. Classical Eurasianism and Its Legacy. Canadian-American Slavic Studies. 34. No 2. 125–39. Brill.

Rangsimaporn, Paradorn 2006. Interpretations of Eurasianism: Justifying Russia’s role in East Asia. Europe-Asia Studies. 58:3. 371–389. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

Shlapentokh, Dmitry 2021. Ideological Seduction and Intellectuals in Putin’s Russia. Palgrave Macmillan. Springer

Kipp, Jacob W. 2002. Aleksandr Dugin and the ideology of national revival: Geopolitics, Eurasianism and the conservative revolution. European Security. 11:3. 91-125. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group

Eltchaninoff, Michel. 2017. Inside the Mind of Vladimir Putin. Pp 91-93. Hurst

Smith, Graham. 1999. The Mask of Proteus: Russia, Geopolitical Shift and the New Eurasianism. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. Vol 24. No 4. Pp 481-494. The Royal Geographical Society. JSTOR

Mondry, Henrietta. 2011. Ethnic Stereotypes and New Eurasianism: Alexander Prokhanov’s Novel “The Cruise Liner Joseph Brodsky”. New Zealand Slavonic Journal. Vol 45. No 1. Pp 147-173. JSTOR

Peunova, Marina. 2008. An Eastern Incarnation of the European New Right: Aleksandr Panarin and New Eurasianist Discourse in Contemporary Russia. Journal of Contemporary European Studies. 16:3. 407-419. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group

Shlapentokh, Dmitry. 1997. Eurasianism: Past and Present. Communist and Post-Communist Studies. Vol 30. No 2. Pp 129-151. University of California Press. JSTOR

Shlapentokh, Dmitry. 2007. Dugin, Eurasianism and Central Asia. Communist and Post-Communist Studies. Vol 40. No 2. Conflict and Conflict Resolution in Central Asia: Dimensions and Challenges. Pp 143-156. JSTOR

Tchantouridze, Lasha. 2001. Eurasianism: In Search of Russia’s Political Identity: A Review Essay. No 16. Pp 69-80. Institute of International Relations. JSTOR

Palat, Madhavan K. 1993. Eurasianism as an Ideology for Russia’s Future. Economic and Political Weekly. Vol 28. No 51. JSTOR

Clover, Charles. 1999. Dreams of the Eurasian Heartland: The Reemergence of Geopolitics. Council on Foreign Relations. Pp 9-13. JSTOR

Sabet, Amr G. E. 2015. Geopolitics of a changing world order: US strategy and the scramble for the Eurasian Heartland. Contemporary Arab Affairs. University of California Press. Vol 8. No 2. JSTOR

Shlapentokh, Dmitry. 2009. History and Interethnic Conflicts in Putin’s Russia. Journal of Educational Media, Memory & Society. Teaching and Learning in a Globalizing World. Vol 1. No 1. Pp 165-179. Berghahn Books. JSTOR

Shlapentokh, Dmitry. 2016. Kazakh and Russian History and Its Geopolitical Implications. Insight Turkey. Presidential System and Turkey Proposals, Debates and Draft. Vol 18. No 4. Pp 143-164. SET VAKFI Iktisadi Isletmesi. JSTOR

Gvosdev, Nikolas. 2002. Moscow Nights, Eurasian Dreams. The National Interest. No 68. Pp 155-160. Center for the National Interest. JSTOR

Bernstein, Anya. 2009. Pilgrims, Fieldworkers and Secret Agents: Buryat Buddhologists and the History of an Eurasian Imaginary. Inner Asia. Vol 11. No 1. Brill

John O’Loughlin, Gearóid Ó Tuathail (Gerard Toal) and Vladimir Kolossov. 2005. Russian Geopolitical Culture and Public Opinion: The Masks of Proteus Revisited. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. Vol 30. No 3. Pp. 322-335. The Royal Geographical Society. JSTOR

Shnirelman, Viktor & Panarin, Sergei 2001. Lev Gumilev: His Pretensions as Founder of Ethnology and his Eurasian Theories. Inner Asia 3. 1–18. Brill

Shlapentokh, Dmitry 2007. Dugin Eurasianism: a window on the minds of the Russian elite or an intellectual ploy? Stud East Eur Thought. 59:215–236. Springer

Bassin, Mark. 2009. Nurture Is Nature: Lev Gumilev and the Ecology of Ethnicity. Slavic Review. Vol 68. No 4. Pp 872-897. Cambridge Univeristy Press. JSTOR

Yalinkilicli, Esref. 2018. Uzbekistan as a Gateway for Turkey’s Return to Central Asia. Insight Turkey. The struggle over Central Asia Chinese-Russian Rivalry and Turkey’s comeback. Vol 20. No 4. SET VAKFI Iktisadi Isletmesi. JSTOR

Ter-Petrossian. 2018. Armenia’s Future, Relations with Turkey and the Karabagh Conflict. Chapter 4 The Karabagh Conflict and the Future of Armenian Statehood. Springer

Bai & S. Wang. 2021. Spirit of the Silk Road. Chapter 2 Connectivity Construction. Springer

Borozna. 2022. The Sources of Russian Foreign Policy Assertiveness. Chapter 7 Geoeconomics and Foreign Policy. Springer

Pamment and K. G. Wilkins; L. Smirnova. 2018. Communicating National Image through Development and Diplomacy. Chapter 11 Ambivalent Perception of China’s “One Belt One Road” in Russia: “United Eurasia” Dream or “Metallic Band” of Containment?. Palgrave Studies in Communication for Social Change. Springer

Peimani, Hooman. 2003. X. Growing Tension and the Threat of War in the Southern Caspian Sea: The Unsettled Division Dispute and Regional Rivalry. Perspectives on Global Development and Technology. Brill

McGlinchey, Eric. 2016. Leadership Succession, Great Power Ambitions and the Future of Central Asia. Central Asian Affairs. Brill

Yuldasheva, Guli. 2020. Iran-Uzbekistan Relations in the Regional Security Context. Asian Journal of Peacebuilding. Vol 8. No 1. 187-202. JSTOR

Lukin, Alexander & Novikov, Dmitry 2021. The Return of Eurasia: Continuity and Change. Chapter 2 Greater Eurasia: From Geopolitical Pole to International Society? Pp 33–78. Palgrave Macmillan.

Dugin, Alexander 2000. On the implementation of the Eurasian Project and National Liberalism. Dugin on Thursday, October 12, 2000–11:59. http://arcto.ru/article/1166?fbclid=IwAR266O_qGDtOcndDFfcg1f5K7i_aTgNDZe94k1l9jpZsZrImxhGPKQ_-hho

Discourse between Yaqub Zaki and Geydar Dzhemal. Political islam, neo-ottoman project, Russia, China. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eTBxNpCHeEg

The curious connection between Shedman and the Caliphate. https://shedman.tumblr.com/post/111458031459/the-curious-connection-between-shedman-and-the

Prof. Dr. Yaqub Zaki, Scotland. A9 Televizyonu. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5PcbMN_lIJo

Dzhemal, Geydar 2012. Trap for Eurasia. http://www.kontrudar.com/statyi/lovushka-dlya-evrazii-31072012

Dzhemal, Geydar 2015. Why Can’t Iran and Russia Be Partners in Real Life? http://www.kontrudar.com/statyi/pochemu-iran-i-rossiya-ne-mogut-byt-partnerami-v-realnoy-zhizni

Dzhemal, Geydar 2007. “Walking Between” Mediterranean, Canpian and Arabian. http://www.kontrudar.com/vistupleniya/hozhdeniya-mezhdu-sredizemnym-kaspiyskim-i-araviyskim?fbclid=IwAR1snZb7t-ZnZ5dgLfaxT92Mi8pW8cyiydXAudtJa1PyYNwnjRUJrybRaUQ

Dzheml, Geydar 2010. Leave To Stay. http://www.kontrudar.com/statyi/uyti-chtoby-ostatsya-12092010

Dzheml, Geydar 2012. Why Do We Need Assad?. http://www.kontrudar.com/statyi/zachem-nuzhen-asad-14022012

Dzheml, Geydar 2011. Lord of the East. http://www.kontrudar.com/statyi/povelitel-vostoka-27092011

Dzheml, Geydar 2014. “With Erdogan, Turkey will take an anti-Russian position and increase support for the Crimean Tatars”. http://www.kontrudar.com/vistupleniya/geydar-dzhemal-s-erdoganom-turciya-zaymet-antirossiyskuyu-poziciyu-i-budet-narashchivat

Sibgatullina, Gulnaz & Kemper, Michael 2017. Between Salafism and Eurasianism: Geidar Dzhemal and the Global Islamic Revolution in Russia. Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations. 28:2. 219–236. Routledge. Taylor & Francis Group.

Shlapentokh, Dmitry 2008. Islam and Orthodox Russia: From Eurasianism to Islamism. Communist and Post-Communist Studies. Vol 41. No 1. University of California Press. JSTOR. USA.

Esref Aydogmus 2018. Erdogan’s advisors were warned pf impending coup attempt – Perincek. https://ahvalnews.com/patriotic-party/erdogans-advisors-were-warned-impending-coup-attempt-perincek#

Shlapentokh, Dmitry 2016. The Ideological Framework of Early Post-Soviet Russia’s Relationship with Turkey: The Case of Alexander Dugin’s Eurasianism. Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern studies, Vol 18. Pp 263-281. Routledge.

Candar, Cengiz 2021. Turkey’s Neo-Ottomanist Moment – A Eurasianist Odyssey. Transnational Press London.

Tuysuzoglu, Gokturk 2014. Strategic Depth: A Neo-Ottomanist Interpretation of Turkish Eurasianism. Mediterranean Quarterly 25:2. Mediterranean Affairs.

Torbakov, Igor 2017. Neo-Ottomanism versus Neo-Eurasianism? Nationalism and Symbolic Geography in Postimperial Turkey and Russia. Mediterranean Quarterly 28:2. Mediterranean Affairs.

Upton, Charles 2018. Dugin Against Dugin: A Traditionalist Critique of the Fourth Political Theory.